Mama Adrienne Goh reflects on Denmark’s marvellous education system, and what Singaporean parents can learn from it

Last year Singaporean mama Adrienne Goh sent us a dispatch about her family’s life in Copenhagen, Denmark, where they’ve lived since 2014. From forest kindergartens to kid-friendly museums, she had us pretty easily sold on the Scandi-life. Her daughter, Sara, is now in third grade, but rather than stress about exams, or spend weekends studying in tuition centres, she focuses on building friendships, learning about empathy, and of course embracing the hygge lifestyle — even in school. Read on for an enlightening reflection on schooling and what we, as parents, could stand to learn about educating our kids, no matter what country we live in.

My daughter is 8 and she is in third grade. She does not understand the concept of exams. Nor grades. Nor “studying”. She is still trying to get through her times tables (horror of horrors); she looks forward to her homework, and she loves school. Welcome to schooling in Denmark.

The Danish approach to formal education starts when the child transitions from kindergarten to school; after all, kindergartens in Denmark are mostly play (in Sara’s case, they prided themselves on being all play). To ease this transition from play to formal education, Danish schools start with an almost cute “Grade 0”. Sara’s Grade 0 was gentle, motherly and still focused on play; in fact, it was an extension of kindergarten but in a school environment. No one in Sara’s class was really expected to know how to read or write — and this meant that Sara (and most Danish children) lived a carefree and enrichment-free preschool life.

I distinctly remember Sara’s Grade 0 teacher, L. Every morning, Teacher L focused on creating a calm class environment, and she acknowledged every child entering the class. If a child was having a particularly unsteady morning, she spent some time reassuring the child. In the initial weeks, where Sara felt overwhelmed, I witnessed teacher L talking to her gently and taking her by the hand.

Classes ended at 2pm, and once I was early and waited outside the classroom. “Class Dismissed” was not simply when the teacher stepped out of the classroom. I realised that Teacher L dismissed the children in batches. Further, Teacher L sat herself by the door, and as the children queued in line to exit, to each of them, she either said a little something, shook hands or hugged. Sara hugged Teacher L every day. To the children, these simple gestures affirmed and validated their first year in school.

The Danish education system continues to surprise me. It is certainly not without its flaws and at times, we have been flummoxed and left wondering, “Why?”. But fundamentally, the Danish approach to education resonates strongly with us. Here are some aspects we particularly like:

The Joy of Learning

There is no drill approach, there is no rote learning, there are no Danish spelling tests to memorise. The curriculum does not feel rushed or compressed, and sufficient time is given for the learning to settle and sink in. Sara’s teachers can spend several weeks explaining a new concept, so the children seem to internalise their learning without being forced to or absorbing more than they can.

Homework is approached with a different perspective. For Sara, homework is not a chore but a…fun challenge. At Grade 0, “monthly homework” consisted of an outdoor activity, playing a family board game and setting the table (why, thank you!). In Grade 1, a piece of homework trickled in once every few weeks — and it had a two week deadline. Its rare appearance meant that homework was almost received with relish at our household.

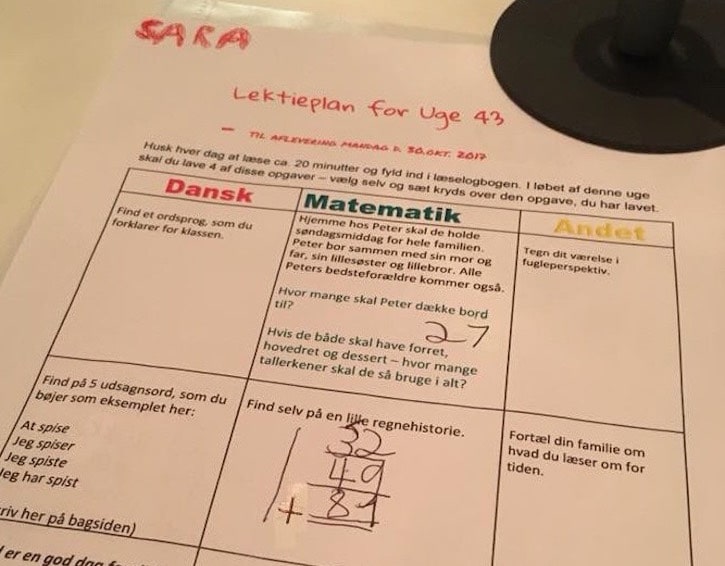

In Grade 2, Teacher S brought “homework” to a whole new level. Every week, the children received a homework sheet with a one-week deadline. The homework sheet contained 9 mini tasks across Danish, Math and “Others”. The children had to choose four tasks to complete, some of which were compulsory. Teacher S explained that by allowing our children to choose, they were encouraged “to take ownership and responsibility towards their work”. Generally, children do not have an issue doing homework when it is their work; when the work feels like the teachers’ work – or worse, their parents’ – problems arise.

The nine mini tasks were also differentiated, giving the children an opportunity to work on those that suited their capability and comfort level. Essentially, this was homework being “personalised”, subtly reflecting the adage that every child learns differently. When we trust children to construct their own ways of learning, we not only help children connect homework to classwork in a more meaningful way, we also help them build up self-confidence.

Up till today, Sara looks forward to selecting her homework tasks. The tasks are varied; they are not mere drills, nor do they involve rote work. Because she is able to personalise her homework, this gives her motivation and interest to complete what is assigned. This in turn lends some meaning to the purpose of “homework”. It is not a “no-homework” policy that matters; it is homework that is worthwhile and that makes sense to a child. This positively influences how a child perceives going to school, and how a child experiences the joy of learning.

Tests and Grades

Contrary to urban myth, there are mandatory Danish national tests, and these start in Grade 2. But these tests could not be more different from what I was used to.

These tests do not aim “to stream” or “to sort” the children according to their grades; teachers use these tests to evaluate how effective their teaching has been, and to identify students who need more academic support.

Read more: Why I’m happy Singapore will stop testing students in P1 and P2

This huge difference in objective cannot be overstated: in Denmark, focus and resources are directed to those who need help. Support is given to children performing “below average”, to help raise their academic levels up to where the national average is. Children from all types of backgrounds have access to the same resources, effectively levelling the playing field. There is little need – or desire, for that matter – for private tuition or enrichment classes, so yes, the private tuition industry is non-existent in Denmark.

To ensure the objectives are met, these tests are not tests the children can memorise or study for. It is not a memory competition; they either know, or they don’t. Sara did not (and could not, even if yours truly forced her to) study for these tests. She had zero stress leading up to test date; my husband was not even aware these tests existed till much later.

The tests are also adaptive, meaning they adjust in terms of difficulty based off whether the child answered the previous question right: this results in a more accurate reflection of the child’s understanding of the material. After the test, Teacher S gave the children individual feedback, and a card with specific areas to focus on. To us parents, teacher S said, “If there is a problem, I will let you know.” (Mic drop.)

When the test objective is “to help” and not “to differentiate”, it brings about a completely different response, from both parents and children (who take their lead ultimately from their parents). Children do not feel overly stressed out, or demotivated by these tests; they do not view grades as a reflection of self-worth or as a point of competition. Instead they learn to develop a healthy view towards the evaluation of their learning, of academic success, and hopefully, this in turn spurs them to continue to learn with joy.

Emphasis on Empathy

“Empathy” has been trending on the hip quotient for a while now, but the Danes have long focused on this aspect and the teaching of empathy is well integrated into the education system.

When Sara was in kindergarten, she participated in a compulsory national programme called “Step by Step”. The children were shown pictures of children expressing different emotions: sadness, fear, anger, happiness, etc. They were then encouraged to describe the expressions and associated feelings. It was a simple but powerful introduction to the basics of developing empathy – learning to recognise, interpret and respect facial expressions and emotions.

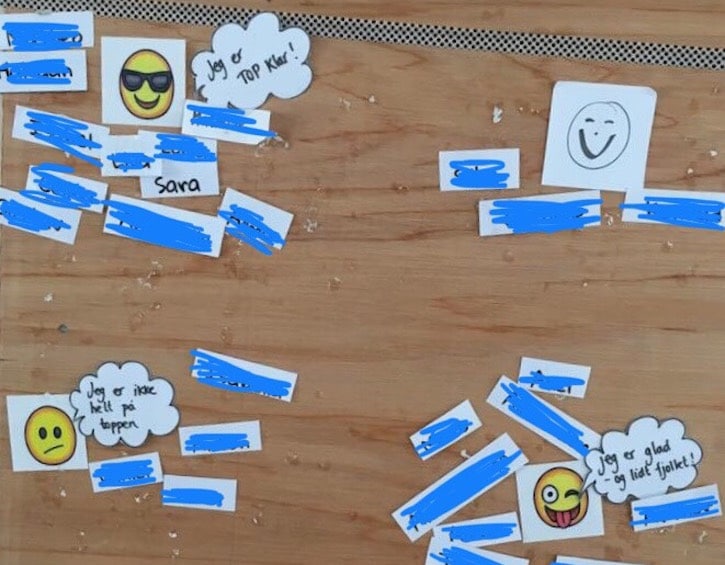

Last year, Teacher S put up a “Mood Board” in class. The children identified their emotions each day, and tagged their names according to the categories – super, OK, playful, sad, happy. Again, a straightforward but useful way to help raise emotional awareness in children. The more we can understand our own thoughts and emotions, the more we can understand someone else’s — we develop our ability to empathise. And when we become more empathetic listeners, we have a higher chance of becoming better…human beings.

And drumroll to possibly one of the most unique and significant parts of the Danish education system … “Klassens Tid” or Class Time. Class Time is scheduled as per the teacher’s discretion, where the class comes together, relaxed and open, to talk about any problems the class may be having. The Danes believe that if children are not functioning well socially and emotionally in class, it is not possible for them to obtain much out of the teaching either, so teachers see value in creating and emphasising a healthy social environment.

Sara’s teachers all had their own way of conducting Class Time. Teacher S gathers the class in front, on the carpet. It is not a one-way street: she encourages comments and opinions, and the class engages in discussions over hot topics. Sometimes, a child needs to get something off his/her chest, and this platform is where it is heard.

One evening, Sara told us that her friend asked Teacher S to tell the class that her parents had separated.

“What did you guys do?” I asked.

“We tried to comfort her. And the others whose parents had also separated, hugged her. She was a bit sad.

(I have also discovered this is very much the Danish way of bringing authenticity to the table – even at a young age. No topic is too “shushed” or “taboo”; they “keep it real”.)

Teacher S concluded the session by teaching that there are many different types of families in this world, and that all families are equal, there is no one type better than the other, and regardless of type, they love their children the same way. (Another mic drop here.)

Collaboration Over Competition

You have probably seen the word “hygge” being bandied around (a lot more than the Danes would like, I suspect). Initially sceptical, I am now a hygge-convert and I can say with 100% conviction that the Danes do hygge like no other.

Hygge is about being together, and making that togetherness a cosy (or as a Danish author describes, “drama-free”) affair, underscored by feeling connected with one another. Consistent with research that high levels of equality translate into happier societies, Denmark’s reputation as an egalitarian society therefore plays an important role as a core value of hygge and “togetherness”.

This emphasis on “togetherness” came as a bit of a cultural shock to the individualistic nature I was more accustomed to. I had grown up placing a huge premium on self-reliance, self-achievement, and the self-made man. Even in a team setting, there were expectations to stand out as an individual. As parents, it is easy to project these “individualistic values” onto our children. Our desire as parents is to want our children to be winners, to be the best at…something.

Every end of the academic year, my social media is awash with pictures of awards our children have won in school – “Best in Science”, “Best in Chinese”, and the most “innovative”. I have come across, “Best in Kindness” (the school shall not be named). These awards can encourage children who have worked hard but on the flip side, it can greatly demoralise a larger proportion of children who have worked hard, but still “failed to win” an award. These awards also serve to heighten the already (unhealthy) competitive environment in some of our schools in Singapore, where children are subconsciously striving to outdo their friends.

There are no such awards in Danish schools. Appropriate praise for hard work and good behaviour is given directly to the child, often in private. The Danes value the social aspect of working together, of team rather than individual achievement. A huge chunk of classwork is organised around group projects and teamwork. It is not a zero sum game, and the joy of knowing that the class is doing well is more meaningful than being the best individual in class.

This emphasis is evident when you peep into a typical Danish primary school classroom. Classroom seating arrangements are in clusters. And more than that, they are arranged such that the children are seated facing one another. You will not see the rows of pairs of tables often found in a typical classroom in Singapore, and where there is cluster seating, tables are often arranged facing the front of the class. (I often wished, staring at the back of my friend’s head during Chinese lessons, for a medusa-type divine intervention.)

Also, the Danish classrooms have swivel chairs which are conducive for pair-work and group discussions. Even if the tasks are not pair/group-work specific, children are allowed to figure out the work together; in fact, they are encouraged to help one another – Sara tells me that the first rule when facing a difficult class task is to seek help from a friend.

Whom you end up sitting with in class is not determined by height (or divine intervention). I learnt that Sara’s teachers put in much time and effort to determine the seating arrangement – children with differing academic abilities are deliberately seated with one another; sometimes, shyer kids with more outspoken ones, calmer kids with more energetic ones.

Coupled with lots of opportunities to carry out group work, the seating arrangement helps the children discover one another’s strengths and weaknesses, and they learn how they can complement one another. To reinforce the importance of collaboration, I know Sara’s teachers take extra effort to recognise how each group works together, how they navigate personal conflicts and overcome their challenges.

Class United

But it does not end here. The Danes take cluster seating a notch up; Sara’s teachers switch the children around after every 8-12 weeks. By the time the year is up, the children would have sat beside, and worked with, many children in class. This has been so beneficial in giving the class opportunities to build new friendships. For Sara, who is more reserved out of the starting blocks, I have seen how sitting and working together with many different classmates has helped her be more comfortable, more confident and more joyful in class.

The more friendships built across the classroom, the more familiar the children are with one another, the less incidence of bullying, and the higher the class social well-being — translating to healthier levels of learning. This may also explain why Sara is fiercely loyal to her classmates, where the mere whiff of negativity in my tone about any classmate (Heaven forbid!) is immediately shut down.

In Grade 0, Teacher L often devoted no less than a third of her monthly newsletters to the social aspect of the class, “evaluating” how well the children were interacting and playing with one another. In the middle of the year, Teacher L highlighted that the children were too focused on playing with their best friends — a clique syndrome was starting. She asked us to encourage our children to be open and inclusive in their play.

And so, I was introduced to “class group-playdates”, a concept used in many Danish schools where 4 or 5 children are purposefully grouped to play together, i.e. the class group-playdate does not comprise the child’s usual playmates. Each child takes turns to host the other children in the playgroup. Playing together is not only a fantastic way to help children make friends, it also “demystifies” an “unknown classmate”, when the children are not yet familiar with one another — further reducing potential bullying.

Perhaps it is more relevant in Denmark, given that the class stays together for the entire duration of their primary and lower secondary education. (The corollary to that is there is no “streaming” of children into different classes based on grades each year.)

Parents are also roped into building class unity: fancy a cuppa at 8am on a school-going morning, in the classroom, with the parents and children from class? Some of us might shudder at that thought, but to further strengthen the relationships between the children, teachers, school and parents, Danish schools host “coffee mornings”.

Coffee mornings are breakfast events, potluck style. They start at 8am and last for an hour. At Grade 0, I did not know what to expect. I was only familiar with coffee mornings in the context of the workplace. I could not think of any reason to be having breakfast with the children and their parents. I mean, my parents had never even stepped into my classrooms throughout my school-going years, much less hung out and had breakfast with me in class.

I remember looking around: at least one, if not both, parents were in attendance. How did they get time off? More amazing was the presence of grandparents (in lieu of parents) and/or tiny tot siblings. (Family friendly, all day, every day). The children were so excited to have their families in class. I felt lost but tried not to look the part. The efficiency-driven Singaporean in me started to surface: What is the purpose of this? What am I supposed to achieve?

“Coffee mornings” are free and easy mornings with your child in class. Some children want to show their classwork to their parents, others do not. Sometimes, the class puts up a little performance, a dance or an exhibit; sometimes, not. And the purpose? As a parent kindly explained, “coffee mornings” are about creating that link between the child, parent and school. Parents need not have a mere “drop-off, pick-up” relationship with the school. It is about creating class unity, it is about building a school community.

A final observation: In Danish schools, there are no prefects or monitors. Perhaps it is a reflection of egalitarianism, where no child has more “authority” or “responsibility” over the other. This extends to the flat hierarchies at Danish workplaces. Moreover, the Danes believe that taking care of one another is everyone’s responsibility (high taxes, hello!). If prefects and monitors are to help enforce school rules, I have discovered that Danish teachers much prefer children learning why a rule exists, and subsequently internalising the rule as a value. They do not want children to obey for the sake of obeying; they believe that building up their core set of values is much more important in the longer run.

Read more:

What this Singaporean family likes best about living in Denmark

Overseas Singaporean Mama Yin Yin Aasheim in Norway

Parenting Tips: Raising Calm Kids in a Crazy World

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All